I’m going to assume you’ve all heard of Miranda rights, correct?

It’s some version of this, depending on the state:

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

- You have the right to an attorney.

- If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you before any questioning if you wish.

In the United States, the fifth amendment reads as follows:

Fifth Amendment

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Miranda addresses the part about not being compelled to be a witness against yourself. You see, back in 1963, Ernesto Miranda decided to kidnap a women, then put his dick some place it didn’t belong.

The police picked him up, questioned him for two hours, and eventually obtained a written confession from him. At no point however, did police tell Ernesto that he had a right to a lawyer.

So armed with the confession, Arizona prosecuted his ass—easily winning their case against him.

Miranda eventually obtained a lawyer, however, who decided that there should be a fucking rule that forces police to advise a person of their rights when they’re arrested. Without that, such confessions should be thrown out, as a lawyer may have advised their client to say or do something quite different from what they actually said and did.

Folks, remember four words if you’re ever being questioned by police: “SHUT THE FUCK UP!” That’s it. SHUT THE FUCK UP!

Ask for a lawyer, and say nothing, no matter what the situation is. Period. Always. Every fucking time. Got it?

It’s not that police are bad, but when you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Police tend to feel like everyone they’re talking to is a bad actor. So on the off chance you might say something that makes them question your innocence, even when you are innocent, you could find yourself in a bad situation because you failed to SHUT THE FUCK UP.

Anyway, Miranda won at SCOTUS and his confession was thrown out, making his trial a mistrial. Since appellate victories don’t trigger the double jeopardy rule, Arizona tried Miranda again, without the confession, and still won.

So while Miranda changed US Law forever—helping innocent people not get railroaded by aggressive government tactics, that fucker was guilty as sin, and his SCOTUS victory didn’t help him one iota.

Now that we’ve covered Miranda, let’s talk about 42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil action for deprivation of rights.

This is a law that says, if government violates your constitutional rights, you can fucking sue them for civil damages.

Miranda and code 1983 are what’s at issue here in this case.

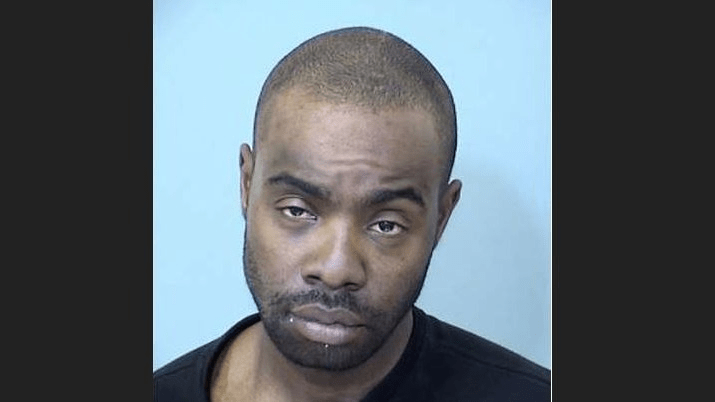

Terence Tekoh was a low-level patient transporter at a Los Angeles hospital.

A young lady was in the hospital, and at one point, under heavy sedation. During that time, she asserted that Tekoh channeled his inner Miranda and stuck a finger in her vagina while she was in the hospital.

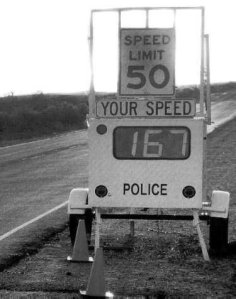

The hospital called the fuzz, and Officer Carlos Vega showed up, questioned Tekoh for some time, without ever reading him his Miranda rights, and eventually Tekow wrote an apology for touching the patient inappropriately, which was deemed as a confession.

However, Tekoh was acquitted in his second trial after an initial mistrial.

I’m not sure how someone’s first hand testimony that he molested them wasn’t sufficient for a conviction, but I guess I have to trust the 12 angry men on this one.

Anyway, Tekoh, feeling like he won the lottery after his acquittal decided to double down and sue Officer Vega for violating his constitutional rights.

He argued that he didn’t vountarily talk with Vega, Vega pulled him aside, called him a bunch of racial slurs, threatened to deport his family, and a whole host of other shit, until he confessed.

I won’t bore you with the lower court shit, just know it made it to SCOTUS, and their question was, is Miranda a constitutional right, and if so, can Tekoh sue if he’s not Mirandized?

Let’s go to the arguments:

First up: Roman Martinez representing officer Vega.

He opened by arguing Miranda is simply a prophylactic rule designed to protect a person’s fifth amendment rights, and is not a right in and of itself. Just because you’re not mirandized, doesn’t necessarily mean your constitutional rights were violated.

He argues that while Miranda helps protect the fifth amendment rights of the individual, if some moron just blurts out a confession before officers mirandized them, you can’t fairly say the cops violated their constitutional rights and coerced a confession.

He argues that Vega merely took Tekoh’s statement. There was no evidence of coercion, courts and juries didn’t feel Vega did anything wrong, Tekoh just blurted out what he had done.

Justice Thomas was the first to chime in, since he has seniority and all. He asked about a previous case, Dickerson V. United States. So let’s discuss that for a minute.

In that case, congress has passed 18 U.S. Code § 3501 – Admissibility of confessions. This statute came about after the Miranda case law was established, and was congress’ attempt to legislate away Miranda rights by saying voluntary confessions given before Miranda rights are given, should be admissible in court.

However, SCOTUS told congress to go pound sand with this shit, and the reason why is very important.

I know I go off on tangents—not even gonna apologize for that. Eat my entire ass if you don’t like it—I’m trying to learn y’all something.

The courts job is to interpret laws, regulations, executive orders, the constitution, and other case law. When they do this, it establishes new case law. But not all laws are on the same tier.

In the case of Miranda, they were interpreting the constitution. The case law they created in Miranda therefore is at the constitutional tier. Congress pass statutes, but they are on a lower tier to the constitution. So while congress could create new statutes to invalidate case law regarding a statute, they can’t write a statute invalidating case law over a constitutional principle, otherwise a law would be trumping the constitution. This is Dickerson in a nutshell. SCOTUS ruled in Dickerson, that congress cannot legislate away constitutional case law.

OK, done digressing, back to the case.

Justice Thomas wanted to know if Dickerson destroyed Vega’s case. If SCOTUS ruled that Miranda couldn’t be overruled solely by statute, then doesn’t that make Miranda a constitutional issue, and therefore qualify it as a constitutional violation?

But Counsel Martinez was like, “Nah, man. Miranda protects a constitutional right, but it isn’t a right in and of itself. It’s constitution-adjacent.”

Justice Roberts next asked:

John G. Roberts, Jr.

Mr. Martinez, if I could focus just for a minute on the language of the cause of action here, 1983.

It gives individuals a right against the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws. Now, under Miranda, you have a right not to have unwarned confessions admitted into evidence.

You wouldn’t have that right if it weren’t for the Constitution.

So why isn’t that right one secured by the Constitution?

Counsel Martinez responded, “Man, a rule to protect a constitutional right isn’t a constitutional right itself. Nowhere else does this occur, that some stupid-ass procedural rule that protects a constitutional right, all of a sudden becomes a constitutional right in and of itself.”

Justice Kagan was the next to chime in. She could not wrap her head around the argument that Miranda is there to ensure the 5th amendment rights are preserved, and that if a Miranda warning isn’t given, that somehow counsel argues that doesn’t necessarily mean his 5th amendment rights were violated.

Counsel Martinez suggested that just because Miranda wasn’t given, could it not be true that cops were having a discussion with him, and he admitted to what he had done in a moment of guilt?

That maybe he wanted to confess, even if he knew he didn’t have to answer their questions?

There’s no reason to assume his confession was coerced at all, without evidence of such. Therefore, his right not to self-incriminate doesn’t have to have been violated.

Justice Sotomayor asked:

Can you tell me why we’re here?

Simple question, but complex reason. She’s asking that Vega not Mirandizing him may have violated his Miranda rights, but it was the prosecutor and courts who chose to admit that confession who royally fucked Tekoh in the ass. So why sue Vega?

Martinez was like, “Fucking Vega lied to the prosecutor and the courts about this bullshit confession he obtained. That’s why we’re going after him. The prosecutor and judge were going on bad info from Vega!”

Next up is Vivek Suri. He’s representing the federal government under Biden, as an amicus, in support of Vega.

His opener was a short banger.

Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court: Miranda recognized a constitutional right, but it’s a trial right concerning the exclusion of evidence at a criminal trial.

It isn’t a substantive right to receive the Miranda warnings themselves. A police officer who fails to provide the Miranda warnings accordingly doesn’t himself violate the constitutional right, and he also isn’t legally responsible for any violation that might occur later at the trial.

He’s basically saying, even if the cop fucked up and didn’t mirandize, the prosecutor brought the evidence in, and the judge allowed it. So why is Vega the asshole here?

Justice Thomas jumped in first again, and simply asked, what if the officer lies about what happened during the interrogation?

Vivek is largely arguing 1983 claims are about things that happen outside of trial. But things that happen during the trial, are generally not 1983 claims, such as ineffective counsel, or other poor actions by the judge and prosecutor.

Vivek essentially argues that the remedy for a Miranda claim, is just to throw out the testimony that was given before a baddie was mirandized. It’s not to make it rain cash on the poor sucker.

Last up is Paul Hoffman, representing Mr. Tekoh, AKA Goldfinger.

He’s arguing that Officer Vega’s account is bullshit. Tekoh did not just willingly give up this info. Vega threatened him with deportation and shit, until he confessed.

Vega then lied and suggested that Tekoh, out of the blue, was just like, “Hey man, I’m sorry, I fingered her without her consent. I’m an asshole. Totally my bad.” As if somehow, he didn’t even feel he needed to Mirandize him yet, but then Tekoh just dropped the dime on himself straight away.

Problem for Hoffman, none of the fucking trials actually found, based on the evidence, that Vega did coerce Tekoh. It’s Tekoh’s story, but that’s it.

If Tekoh just blurted out his guilt willy nilly, Vega really didn’t do anything wrong. But Hoffman needs to prove that Vega threatened him with deportation and such, and he just doesn’t have any court findings or testimony to back that shit up.

Think of it like three steps. The use of an unMirandized statement is a violating of the fifth amendment. 1983 let’s you sue for damages if your rights are violated. If Vega lied and said the confession wasn’t coerced when it was in fact coerced, and that confession was admitted into evidence, than Tekoh’s constitutional rights were violated by Vega, and Vega should be rewarded with some 1983 dollars.

If Vega is telling the truth, and Tekoh just sang like a canary because he was feeling guilty, as Vega suggested at trial, then Vega didn’t coerce that confession, he’s just reporting what he heard Tekoh say.

Since Tekoh was exonerated, you might wonder what harm he is claiming. The confession didn’t help the government convict Tekoh. But Tekoh’s claiming that the fact his confession was used as evidence against him, led to him having to endure a trial at all, and therefore he was harmed.

Hoffman is arguing that Tekoh’s life and reputation were harmed by all this, and none of it would have happened, had Vega Mirandized him, instead of interrogating him. And that’s what 1983 is there for—violations just like this.

The opinion, written by Justice Alito, and joined by the other 5 Republican appointees, decided it didn’t give a fuck whether Vega lied or not. That Miranda is not a constitutional right, it is a prophylactic rule that merely protects a constitutional right. The remedy for a Miranda violation is the evidence not being allowed into trial. It isn’t 1983 dolla dolla bills y’all.

Essentially, he’s saying that because it’s possible Tekoh just blurted out his confession, and Vega was in earshot of it, which would be admissible in court, that this proves that not mirandizing someone isn’t always a fifth amendment violation.

He wrote:

A violation of Miranda does not necessarily constitute a violation of the Constitution, and therefore such a violation does not constitute “the deprivation of a right secured by the Constitution” which is necessary to secure a 42 U. S. C. §1983 claim.

So Tekoh can go fuck himself, instead of his patients—he’s lucky he was acquitted.

Justice Kagan wrote the dissent. I’ll summarize it this way. “If Miranda is required to protect someone’s 5th amendment rights, and a Miranda warning isn’t given, someone’s fifth amendment rights were fucking violated. Alito, respectfully, you’re a crusty old senile fuck, and you should retire.”

![shariah-law[1]](https://logicallibertarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/shariah-law1.jpg?w=300)

![SundayAlcohol[1]](https://logicallibertarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/sundayalcohol1.jpg?w=300)

![US_Park_Police_badge[1]](https://logicallibertarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/us_park_police_badge1.gif?w=244)

![EC689123235C04BEBFE698A4CC_h231_w308_m5_caksoayGp[1]](https://logicallibertarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/ec689123235c04bebfe698a4cc_h231_w308_m5_caksoaygp1.jpg?w=300)