If you’re reading this, I’m going to assume you’re aware SCOTUS overturned the Roe v. Wade decision in 2022, returning the issue of the legality of abortions to the states. This then meant it was no longer a constitutional right, by precedent, for a woman to have an abortion. If you didn’t know that, sorry to hear you were in a coma, but glad you seem to be recovering.

As a result of that decision, this case, along with many others that address abortion rules and regulations, now became up for debate.

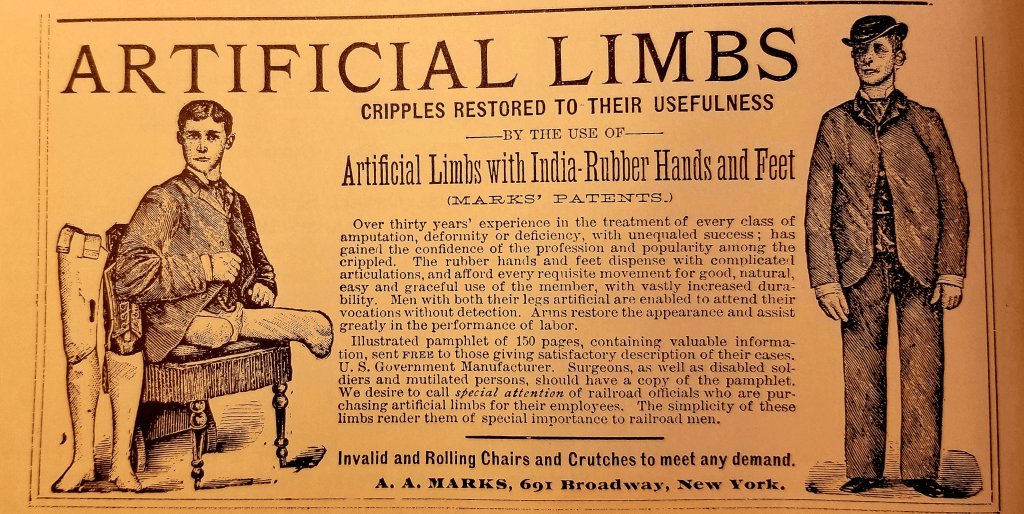

This particular case is about Mifepristone—a commonly drug used to induce a woman to have an abortion by breaking down progesterone in her body, which then causes the uterine wall to become detached, and the fertilized egg/fetus connected to it, to detach from the uterus. A second drug then causes contractions that flush all of that out.

It was approved, under a lot of contentious debate, by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000 for this purpose, and is used in over half the abortions performed in the US.

Initially, the drug required the patient go to the hospital and be administered by a doctor, while under supervision, in case an emergency arises. The reason for this requirement was that many were concerned that there would be complications when used, that may need to be immediately treated at the emergency room. Therefore, they didn’t want it to be given outside a hospital setting.

But here’s the rub, the FDA gathered a LOT of fucking data since then, as they do, and women weren’t having any real problems taking mifepristone. As a matter of fact, it’s shown to be safer than most commonly used drugs, like Penicillin or Viagra. I’m sure there were outliers, but by and large, that shit was uneventful, other than the intended event, anyway.

As you can imagine, having to go to the hospital and then stay there while under observation, for a drug that shows almost no danger, is expensive. It clogs up hospitals, and causes excess expense to the women who choose to have an abortion, may of whom are low income, which is why they’re getting one in the first place.

So in 2016, the FDA allowed it to be prescribed by a doctor, so they could use it in the privacy of their own home. This may seem like no big deal, but have you seen an abortion clinic? It’s wall to wall asshole protestors intimidating, scaring, and even attacking both doctors and patients alike.

Hell, they’ve sometimes even opened Crisis Pregnancy Center clinics next door, making them look like they’re abortion clinics, hoping abortion seekers come to their location by accident, where they can shove god up their ass, lie to the them about the dangers of abortions, and hope they bullshit these folks into changing their mind.

So this new regulation, in the immortal words of the famous philosopher Biden, “is a big fucking deal.” It protects women and healthcare practitioners alike, by protecting medical anonymity, as they should.

Then in 2021, when COVID was fucking everything up, they also allowed it to be distributed by mail-order pharmacies after being prescribed by online doctors.

As you can imagine, anti-abortion folks were like, “Wait a fucking minute!” They were not OK.

Despite the FDA’s findings, because of their bias against abortions, they continued to hammer home the idea that it should not be given outside a hospital, for the reasons cited. Forget the fact that the evidence is against them, they’ve got God on their side. God would want them to lie and mislead people to prevent abortions, which he never mentions in the bible once.

I know I attack them unmercifully, but here at Logical Libertarian, we’re both pro-science, and anti-zealotry. So they fucking deserve it.

I concede, there are perfectly fair, valid, and ethical reasons to oppose abortion. It is inarguably a human life being ended. If folks really believe in fetal personhood, and that’s their sole argument, while I don’t agree, I can and will respect that.

But when they make misleading arguments, lie to people, or manipulate them, just for their own political gain, like the ones about risks that just aren’t there, I take issue with that. Bad science should never be tolerated.

It’s frankly far too difficult to have a fair and honest discussion about abortion in this country. I won’t rehash it here, I already wrote about this shit before. So back to the case.

In comes the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM). Might sound like some fancy doctor group and shit, but it’s literally just a group of Christian doctors who came together, founded a political “company” which does nothing but fight abortion rights, in Amarillo Texas. It’s conveniently next to one Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s district, a Trump appointee who is rather pro-life. And they conveniently filed in that district, since that’s where their bullshit office is located. But no fair argument can be made that this is just some rando group of doctors, who have some actual business in Amarillo, and are bringing this case out of nowhere. This was clearly planned.

So once this judge put a hold on the drug, based on, and I shit you not, blog posts and studies that were withdrawn from medical journals for ethical and methodology reasons (meaning, they weren’t legit studies), the 5th circuit, who make our current conservative SCOTUS look like Bernie Sanders, affirmed his decision.

But then SCOTUS were like, “Whoa, cowboy. Are you guys fucking nuts? You’re making us on the right look bad with this shit!”

So they put those decisions on hold so they could decide this shit themselves, leaving mifepristone still legal again, until they handed down a decision.

Caution, political argument: If we have to mislead people to get them on our side, we’re probably on the wrong side. The majority of the American public, in poll after poll, are pro-choice under reasonable circumstances, like the ones set forth in the Roe v. Wade decision. So these pro-life groups hide behind misleading names and bullshit arguments to achieve their goals, instead of being open and honest, because they know, they’re just on the losing side of the debate.

Anyway, sorry. I was rambling…back to the case.

AHM decided they’d sue the FDA, and argue the safety issues, which the FDA already overcame, and hope they could convince nine justices to forget all about that science shit, by claiming more research was needed. It isn’t.

So there were a few questions before the court.

First: does AHM even have standing? You’ll hear this “standing” thing a lot in SCOTUS cases. It means, were the people bringing the case harmed by the FDA’s decision in some way that requires a remedy, or are they just butt-hurt little bitches who don’t like the decision. If the answer is no, they don’t have standing, and the other arguments become irrelevant.

Second: Was the FDAs approval arbitrary and capricious? Also a very common argument. In a nutshell, it just means the FDA had no reason for their determination, they just did it because they wanted to. But again, they did have a reason…fucking data.

Third: Was the district court right to give them relief? Prior to getting to SCOTUS, a judge and the 5th circuit did put the sale of mifepristone on hold, agreeing with AHM’s arguments, which is why we’re here on appeal.

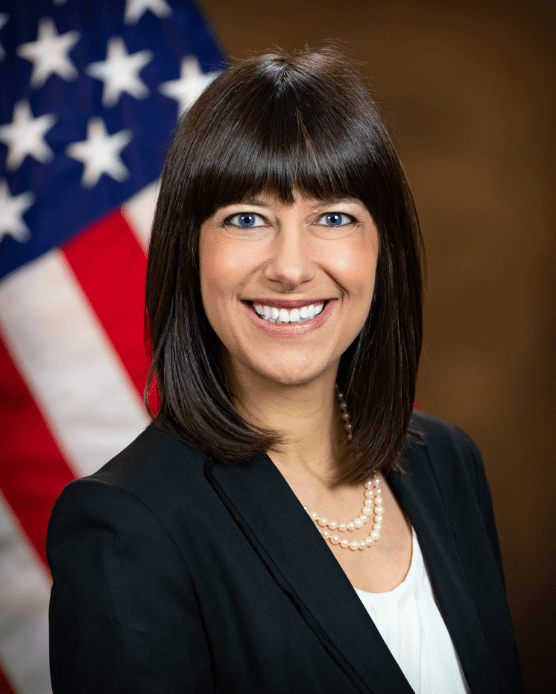

Up first, for the FDA, is SCOTUS veteran Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar.

She pulled zero fucking punches, opening with saying, “Listen, these assholes have no reason to be here. This isn’t their fight, and not one of those motherfuckers will see any harm from these FDA rulings. So they don’t have standing, and they damn well know it.

Even if they do have standing, their argument is shit. We have lots of fucking data showing how safe mifepristone is, and therefore, the rule they want is draconian and stupid.

We all know, these assholes are just trying to backdoor a way to make it more difficult for a woman to get an abortion, right?

Lastly, if you give in to these assholes, in states where abortion is legal, you’ll make it so that women may end up doing riskier surgical abortions, causing more harm than to the women these assholes say they’re protecting.

As such, we invite AMH to eat our entire ass. Thank you.”

Justice Thomas, being the elder statesman, goes first. He asked simply, if AMH doesn’t have standing, then who would?

She was like, “Certainly not these assholes. They don’t take the drug, they don’t prescribe the drug, they’re not forced to administer the drug.

If anyone would have standing, it might be mifepristone competitors who feel it was unfairly approved while their shit wasn’t.

Justice Alito, jumping on Justice Thomas’ argument was like, “What about some doctor in an ER somewhere, a woman comes in, having taken mifepristone, is now having complications. And in order to save her life, the doctor must perform an abortion of an otherwise viable fetus. Can that doctor sue?”

General Prelogar was like, “We’ve looked at 20+ years of data. That hasn’t happened, in the tens of thousands of cases reviewed. So, it’s a stupid hypothetical, and you can fuck right the hell off with it. But sure, I’ll play your stupid fucking games. When that happens, that shit doctor can sue here.”

So again, Alito was like, “shouldn’t there be someone who could sue over this regulation?”

She responded, “Just because we can’t think of someone who wouldn’t have standing, doesn’t mean these assholes do have it. Capiche?”

Interestingly, she cited a case, Clapper v. Amnesty International, where one Justice Samuel Alito wrote the majority opinion, where he specifically stated, just because we can’t think of someone who’d have standing, doesn’t mean these assholes have it.”

I’m sure the irony wasn’t lost on him, and he probably stewed on the fact that she used his own words against him for the rest of the day.

If the FDA’s rules were different, for instance if doctors were forced to prescribe against their will, or patients who sought other treatments pushed into using mifepristone, you could see some argument for harm being done to them. But since that isn’t the rule, those are just hypotheticals that aren’t based in reality.

She then went on to say, if the FDA had gotten it wrong, and mifepristone were harming people, those people would have standing. But they’d also have tort law to go after the makers of mifepristone. And guess what, mifepristone hasn’t been hit with these suits, because the fucking drug is safe.

The problem for these assholes across the aisle, is it isn’t hurting anyone (except the fetus). The FDA got it right, there’s no one who is harmed, thus no one has standing to be sue over this shit.

Not to mention, doctors can’t have standing here, because they are never required to prescribe any drug. This is America, bro! Freedom and shit.

Before I go into Amy Coney Barrett’s next question. We should explain a few things. In the US, we have a law called The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). This law, is the reason why a hospital must treat you, if you go to the ER, regardless of whether you can pay. They must only save your life, not treat you for non-life-threatening situations.

So Justice Barrett asked, “What about EMTALA, can a doctor, faced with a women who’s going to die if she doesn’t get an abortion, refuse to do the abortion? For them, it’s a dilemma. They’re ending one life to save another.”

But general Prelogar made it clear, that hospitals ask doctors in advance if they have such objections, and staff accordingly, so this situation never occurs. As such, while it’s an interesting objection, it currently has no basis in reality. No doctor, will be forced to provide an abortion.

She then asked general Prelogar, what about other cases where they’ve shown that regulations might cause these groups like AMH to have organizational injuries. Like they may have to do extra paperwork or processes to comply with the regulation. What about that? Isn’t that an injury.

Again, general Prelogar was like, “It would be if it were true. But these assholes at AMH don’t have to do a damn thing because of this regulation. So, this is a useless question. Their expenses are entirely self-afflicted, in an attempt to win this case.”

Justice Neil “Golden Voice” Gorsuch chimed in and asked about the principle of “offended observer standing?” This is something Gorsuch, and Justice Thomas have quashed before. But some courts still seem to want to offer some notion of distress or offense as an injury. So justice Gorsuch, not defending offended observer standing, wanted her to opine on it nonetheless.

General Prelogar responded that in those instances, the government did something directly to the person that offended or distressed them. In this case, government merely removed a restriction on a drug. So it wasn’t an action taken against anyone. Therefore, that argument is fucking stupid.

Justice Alito, seemingly still skeptical, asked, what about a study that suggested that there were more ER visits from women who received mifepristone outside the hospital?

General Prelogar pointed out, that this doesn’t suggest, on it’s own, that women were experiencing more adverse effects. It just shows, that if a woman takes it without medical supervision, she may experience normal reactions to the drug, that worry her, so she goes to the hospital to make sure she’s OK, and they confirm as much. Most of the additional visits weren’t treated for any condition. The hospital just confirmed they were OK, and sent them home.

For the merits of this case, what matters is whether women had more adverse effects from the drug, which they didn’t.

Justice Sotomayor chimed in and asked, “while the more ER room visits is concerning, whether the rise is deemed a sufficient safety risk is up to the FDA to determine, right?”

General Prelogar confirmed it is, then again hammered home, that adverse affects is what actually matters, and their studies showed no real increase of those.

She went on to point out, that the FDA also considers the burden on the health care industry. They created this rule, not just because mifepristone was quite safe when taken without medical supervision, but also, that the need for medical supervision created an unnecessary burden on the healthcare system. This rule actually makes healthcare safer, because someone might die as a result of a doctor being busy watching a woman take a drug that was of little to not threat to her, instead of being available to help a truly at-risk patient. Not to mention, all the dangers from pro-life activists.

Justice Jackson chimed in with a phenomenal question for the respondents, however, she was still speaking with petitioner’s counsel. Not that she didn’t know that, but she was basically testifying for the petitioner, and getting general Prolegar to agree with her.

She asked, “Since these assholes are claiming an injury of conscience, where they’re being forced to participate in a process they oppose to on moral grounds, it would make sense to provide them an exemption. But you state they already have that, under federal law. So what they’re asking for, is to not only have to participate, but to prevent others who aren’t morally opposed to also be unable to participate.

General Prolegar was like, “You’re speaking my love language, KBJ!”

Next up is counsel Jessica Ellsworth, Representing Danco Laboratories.

What the fuck do they have to do with this? They make mifepristone. So they are here supporting the FDA’s side, and their drug.

She opened by laying out the absurdity of the respondent’s claim. Remember, that they argue they do have standing, if a doctor must perform an abortion, after someone has used mifepristone without medical supervision, in order to save the mother’s life. Let’s review what would have to happen for this to be true:

- The drug would have to fail to work as intended. It doesn’t.

- The patient would have to have a severe adverse affect that harms the mother. But that isn’t happening.

- If they had such an adverse effect, it would somehow cause a severe risk to the mother’s life, yet the fetus would still be viable. This also isn’t happening.

- The doctor would have to work at a hospital where no other pro-choice doctor is available. But the hospital’s hire in such a manner as to ensure this doesn’t happen.

- If the they were somehow the only doctor on duty at the time, the doctor would then have to perform an abortion procedure under EMTALA. Again, the doctor does have that right under federal law, to refuse to perform a service they morally object to.

Justice Thomas mentioned the Comstock Act and it’s ramifications. This is a law that’s older than your mom, or your mom’s mom. It’s from 1873, for fuck’s sake. You remember, the time when society was very repressed and people walked around with crucifixes up our poop shoots?

These Christian zealots wanted to ban anything that went against their Christian values. The law was drafted by one grade A, Christian fundamentalist asshole, Anthony Comstock, a man who surely never encountered a party he was invited to.

I can’t believe this stupid law is still even on the books. But anyway, it specifically prohibited sending sexually explicit materials and contraception or abortion aids in the mail.

I know what you’re thinking. Then how did I get that mega pack of condoms from Amazon in the mail?

Well, the law has been revised now and again, and for the most part, it’s been construed as limiting those things, if they’re illegal in the state it’s being mailed to. But let’s be honest, the law just needs to go. We’re way past this shit, now. It absolutely violates the fuck out of the first amendment.

Ironically, it may still be law, because it’s rarely enforced, and thus no one has standing to challenge it, because no one gets harmed since they don’t enforce it.

Counsel Ellsworth was like, “Listen, that fucking law hasn’t been enforced in nearly 100 years. So why start now?”

Justice Alito, seeming rather skeptical of counsel Ellsworth and her company’s motives, was seeking first to understand why they’re an amici. He rightly questioned if this is about money for them, as they’ll presumably sell more if the restrictions before 2016 are reimposed.

She agreed.

He then went on a tangent about asking if the FDA’s data is beyond question, and do they ever fuck up.

I don’t think he understands how the FDA works, but for the cheap seats, they don’t just approve something and let it ride. They continue to monitor these drugs, and if new evidence comes to light, they reevaluate their decisions accordingly. This is the scientific method.

And frankly, even if they do fuck up, some justice in a robe, is not the person to determine they fucked up. That’s for medical researchers, which the FDA has falling out their assholes. Know your role, Alito!

I think Alito’s argument was that the FDA could’ve fucked up, and that the AMH may have a valid argument. But the FDA have evidence, and the AMH have none. So we don’t bias towards those without evidence in science, any more than we should favor such things in court.

It was frankly, a poor line of questioning from Alito, in my humble opinion. But understandable from someone without a science background, or an understanding of FDA operations.

It’s also worth noting, if AMH were to win on the merits, it would undermine the entire FDA approval process, and every single drug approved for use in the US. Because now, any doctor with beef about a drug, can get the courts, who did zero science and are not scientists, to overrule the FDA, an organization of scientists who are trained to understand the dangers, safeness, and efficacy of drugs.

For instance, if a doctor who thinks people who use pain pills are all addicts who need to suck it up, then they could try to ban all pain pills. Hopefully, you see the problem here?

Justice Kagan then asked about the adverse effect reporting Danco was beholden to. That they were held to a higher standard of reporting.

Justice Kagan’s referring to the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

Counsel Ellsworth noted that before 2016, prescribers had to report their adverse events to Danco, and Danco then reported to the FDA. But in 2016 when they changed the rule, they aligned it with the approximately 20,000 other FDA approved drugs, based on it’s safety record. She didn’t explain what changed, but I assume Danco no longer had to be in the middle.

Justice Jackson, shitting on her own branch of government was like, “Do you worry about us law nerds opining on you medicine and pharmacology nerds, and the shit you do, that we clearly don’t fully understand?

Counsel Ellsworth reminded them that the lower court, in the ruling for AMH, relied on citations of anonymous blog posts (not science), and other debunked or flawed studies the FDA would never accept as evidence, because their methodology was so flawed, no scientists would ever consider them good science.

She went on to respectfully point out that this isn’t the expertise of the courts, and that’s why they should rely on the FDA here.

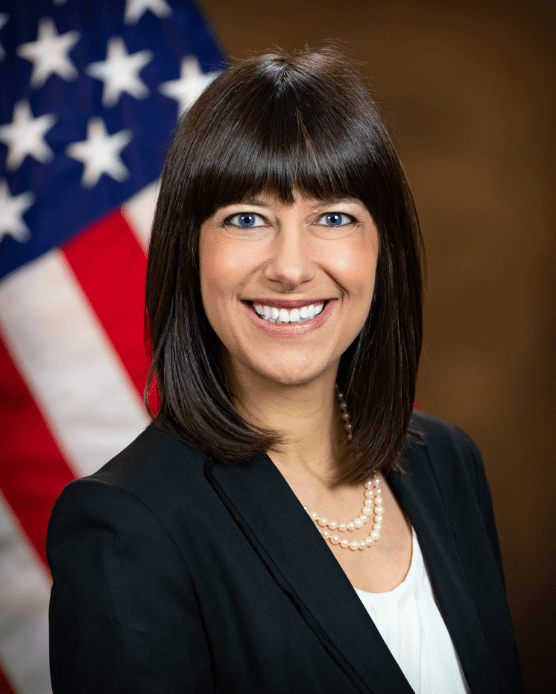

Last up, for AMH, counsel Erin Hawley

If her name sounds familiar to you, she’s the wife of Senator Josh Hawley. A pro-life match made in heaven.

She started off by citing the the increased ER visits noted (and debunked) before, suggesting mifepristone has a significant increased risk when not taken under medical supervision.

She then went on to explain why she feels they do have standing, but her arguments, frankly, make little sense in that regard.

She essentially walked into the petitioner’s trap, by reciting the thing about all the things that would have to be true for them to be harmed, as if that wasn’t an absurdity, when the opposition showed it absolutely is.

Justice Thomas was like, “What’s your harm here? You claim additional time and resources, but as near as we can tell, that’s all self-imposed. The additional time and resources used, are just you here fighting this shit.”

She was like, “No, dawg. These doctors are morally opposed to doing an abortion. And this fucking rule might put them into a position where they have to either perform an abortion or let a woman die. That’s some grade A bullshit!”

Again, this was disproven by the petitioners, but that was her argument, and apparently she didn’t have a backup plan.

She then went on to colorfully argue, that now that they’re allowing this drug to be prescribed without medical supervision, their organization has had to divert from their mission of creating a pro-life society, to explaining the dangers of abortion drugs. You know, the dangers that the FDA have a shitload of data suggesting are not harmful at all?

I’m sorry to be so obviously biased here, but again, while I respect the basic pro-life position on it’s face of just wanting to preserve human life, these arguments are trash. They’re desperate attempts to win an argument they know they lose when they’re honest about the merits. It’s pathetic.

Justice Jackson chimed in with the “Show me the money” question. She was like, “where exactly did this injury occur to the doctor from the AMH group?”

Counsel Hawley started to provide a hypothetical scenario where it would happen, but justice Jackson shut that shit down immediately. She was like, “I don’t want a hypothetical. I want you to show me actual harm your clients incurred. Do you have any?”

She was like, “No, but that doesn’t mean we won’t in the future.”

Justice Jackson was like, “if we ruled, that a doctor will never have to be faced with this extremely absurd hypothetical situation you describe by law, is that good enough?”

Counsel Hawley was like, “Fuck no. These are emergency situations. When the doctor is called and scrubbed in, they may not know that’s the situation. So for them to find out, object, scrub out, and attempt to bring another doctor in, puts the patient at added risk. That’s what we’re worried about.”

Justice Jackson was like, “So because of this highly unlikely scenario, you want to ruin this shit for everyone else because your people are pro-life zealots? I’m sorry, but you’re an asshole.”

Justice Gorsuch, tagged in for Justice Jackson, and was like, “Listen. When we provide a remedy, it’s supposed to be for your clients, but we typically don’t offer a remedy that goes above and beyond that.

For instance, your client lost a thousand bucks, we don’t give them a judgement for two thousand.

So what you’re seeking is a little unfair, is it not?”

Justices Gorsuch. Roberts, and Jackson’s all then asked questions wondering why the fuck are AMH wanting to ruin it for everyone else, when we can offer a remedy just for them…the one they already have by law, where they can refuse to do the treatment.

She really didn’t have a new response. She felt the conscience objection, in and of itself, was sufficient.

Justice Gorsuch then asked about universal injunctions.

What’s that you ask?

It’s when the court forbids government from enforcing a law against anyone, not just the people who got the injunction, which is what she’s asking for here.

Justice Gorsuch was like, “This was never done during Roosevelt’s 12 years in office, and over the last four years, maybe 60 times around the country by lower courts. But we’ve never done it. So what makes you so fucking special?”

Here response was essentially that her side deserves relief, and she feels it’s the only way they can get it, via this desired universal injunction. So that’s what makes them special.

Justice Kagan went on the warpath, next.

Channeling her best Law & Order “gotcha” skills, she was like, “We agree with standing rules, right?”

Counsel agreed.

So she then asked, “if you had to pick one of your asshole clients as the person who has standing here, who would it be?”

Counsel named two of the doctors.

Then Kagan was like, “So what fucking imminent injury are these two assholes facing if we rule against them?”

Her response again was a “harm of conscience.” That the doctors not only object to performing an elective abortion (elective just means, not an abortion to save the mother’s life, just an abortion to end the pregnancy because she doesn’t want to have a child), but also, they are morally opposed to finishing a procedure of that nature. For instance, if there were complications after the pregnant women takes the mifepristone.

So then, Justice Kagan was like, “Has she ever had a situation where this occurred to her?”

Counsel replied it had. That the doctor was asked to do a dilation and curettage procedure that was life threatening to the patient.

Justice Kagan then asked, “Did she object, and invoke her right to refuse?”

Counsel replied that there wasn’t time. It was an emergency, and she either did the procedure, or the woman would have likely died, had she opted out and sought another doctor in the hospital to do it.

Justice Kagan, seemed rather skeptical. Arguing that they didn’t make their objection known, they just decided to proceed and help the patient. So it must not bother them that fucking bad.

To Kagan’s point; imagine a neo-Nazi shoots up a Jewish school, gets shot doing it and goes to the ER, the doctors still treat the murderous fuck. Things like this happen all the time. Doctors treat someone they almost assuredly wish would die.

So the idea that they can’t help a desperate pregnant woman who just doesn’t want to see her life fall to shit, deal with complications from taking mifepristone? Give me a fucking break.

But again, counsel hammered home the idea, that it was a dilemma she was faced with, which didn’t provide her time to avoid. She had no way of knowing what she was walking into, and getting someone else to handle it in a timely manner.

Justice Alito threw counsel a bone, when he pointed out a New York voting district case. The courts gave standing to a political group because there was a citizenship question on the census document they tenuously argued would cause them harm. They knew that a certain percentage of citizens wouldn’t fill out the form because that question was there, which would then mean, New York would count fewer citizens than it actually had, leading them to potentially losing a voting district (electoral vote).

So if that convoluted set of “maybes” was good enough for standing, shouldn’t this be?

Counsel was like

Justice Sotomayor, however, was in no “bone throwing” mood with this shit. She went on to ask, that if it’s illegal in these states anyway, then what’s her point? The “injuries” these doctors incurred appear to be before Roe v. Wade was overturned, so they’re essentially claiming that they were injured before when abortions were allowed, so shouldn’t they assume they won’t be in the future?

Counsel Hawley responded that many of these women go out of state to get the prescription, buy the pill, take it, and go home, where the complications then occur.

Justice Barrett jumped in and noted that the two doctors she mentioned never actually terminated a fetus, which is what they claimed their opposed to.

Her response was that it was a broader conscience harm, meaning, she felt she was participating in the abortion process, even if she didn’t specifically terminate the fetus.

Under questioning from multiple justices, she also wanted to point out that requiring in-person visits gives the doctor an opportunity to do an ultrasound and detect complications before they become emergencies.

But as was made clear earlier, the increase was only to ER visits, not actual emergencies. Many were simply women worried about what was happening, and not experiencing life threatening.

Justice Barrett then questioned her on the financial harm she incurred. But again, they all seemed related to the expenses they racked up fighting this regulation, and not regulations they incurred from just doing what the FDA advised or walking away.

She tried to mention studies and such they performed, but they were all to make the case here, not costs they endured just by following the FDAs guidelines. So hard to really call that an expense, as it’s self-inflicted damage.

In the US, we don’t typically let people consider legal expenses, damage. Especially, when they’re the ones who instigate the litigation, and weren’t harmed otherwise.

Anyway, to wrap things up, solicitor general Prelogar was allowed a few minutes of rebuttal where she shit all over counsel Hawley’s claim these doctors incurred an ounce of fucking harm to give them standing.

I’ll let Prelogar wrap it up in her own words.

Thank you. On associational standing, Mr. Chief Justice, you asked where do you cross the line to get to a certainly impending injury.

One thing the Court has looked at is whether that harm has materialized in the past and how often.

Now it doesn’t always guarantee there will be a future injury, but it can be a source of information.

And, here, what is so telling is that Respondents don’t have a specific example of any doctor ever having to violate this care in violation of their conscience.

Instead, Respondents have pointed to generalized assertions in the declarations that never come out and specifically say by one of their identified members: Here’s the care I provided, here’s how it violated my conscience, and here is why conscience protections were unavailable to me.

The fact that they don’t have a doctor who’s willing to submit that kind of sworn declaration in court, I think, demonstrates that the past harm hasn’t happened, and the reason for that is because it is so speculative and turns on so many links in the chain that would have to occur and at the end would be back-stopped by having the federal conscience protections in play.

On organizational standing, my friend has pointed to the fact that they invested time in preparing their citizen petition.

She says they voluntarily conducted studies and then generally refers to diversion of resources.

If that is enough, then every organization in this country has standing to challenge any federal policy they dislike. Havens Realty cannot possibly mean that.

The Court should say so and clarify it is at the outer bounds and Respondents don’t qualify under that standard.

On remedy, Justice Gorsuch, Justice Jackson, you pointed out the striking anomaly here of the nationwide nature of this remedy. Justice Jackson, you suggested maybe a more tailored remedy to the parties protecting their conscience protections should have been entered.

The problem here is they sued the FDA. FDA has nothing to do with enforcement of the conscience protections.

That’s all happening far downstream at the hospital level.

And the only way to provide a remedy based on this theory of injury, therefore, was to grant this kind of nationwide relief that is so far removed from FDA’s regulatory authority that it’s ultimately requiring all women everywhere to change the conditions of use o f this drug. And I think it’s worth stepping back finally and thinking about the profound mismatch between that theory of injury and the remedy that Respondents obtained.

They have said that they fear that there might be some emergency room doctor somewhere, someday, who might be presented with some woman who is suffering an incredibly rare complication and that the doctor might have to provide treatment notwithstanding the conscience protections.

We don’t think that harm has materialized.

But what the Court did to guard against that very remote risk is enter sweeping nationwide relief that restricts access to mifepristone for every single woman in this country and that causes profound harm.

It harms the agency, which had the federal courts come in and displace the agency’s scientific judgments.

It harms the pharmaceutical industry, which is sounding alarm bells in this case and saying that this would destabilize the system for approving and regulating drugs.

And it harms women who need access to medication abortion under the conditions that FDA determined were safe and effective.

The Court should reverse and remand with instructions to dismiss to conclusively end this litigation.

In a unanimous decision, authored by Justice Kavanaugh, the FDA prevails by demonstrating that AMH has no standing to bring this to court. They won’t be harmed in any way by a woman taking Mifepristone in an effort to perform an abortion.

Standing may seem like something the court does, just to get out of making a decision, but the implications are a “separation of powers” issue. If a plaintiff doesn’t have standing, then it’s effectively the courts just weighing in on a political issue, which isn’t their job.

AMH, if they want this achieved, must convince congress and the president to make it a law. That’s why requiring standing is a thing.

By requiring the plaintiffs have standing, the courts are addressing a specific person being harmed, and attempting to remedy that harm, if they get a judgment, which is the role of the court.

While this may seem like a huge victory for abortions, it should be understood that all this does, is protect its access in states where abortions are legal. There will still likely be prohibitions on prescribing it in states where abortions are banned.

Hear oral arguments, or read about the case here.

With this case, I also used information obtained by a couple SCOTUS-themed podcasts. You can give them a listen if you like.

Strict Scrutiny covered it quite well

So did Amicus

While these podcasts tend to be more supportive of the view from the left, they do a good job covering the courts, and those of us who are more biased towards liberty are adult enough to handle opposing opinions aren’t we? Good good.