Ever heard of the Chevron Oil Company? They’re kinda a big fucking deal in big oil.

Well, they were also kinda a big fucking deal in America’s court system.

Before we get into Loper and Raimondo, our case for today, we have to understand why Chevron was such a BFD in the courts. It goes back to 1984 landmark case, Chevron U. S. A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.

No one knew at the time, that it would be a landmark case, initially, it was your basic snooze fest. But, it has since been cited in other cases over 18,000 god damn times.

Was Chevron a fascinating case with a compelling opinion? That’s a big nope. And, since this isn’t our case today, I’m just going to give a simple overview.

But before we get into that, we need to explain a distinction I don’t think I’ve covered before.

In the United States, we tend to think that congress are the only people who write laws. While this is the framework the constitution lays out, it gets complicated.

The word law, for our purposes, is a generic term that basically encompasses anything the government has created to control, regulate, or restrain itself, or the people. But, there are five types of things that carry the weight of law, which have different purposes.

- The Constitution: It is the document creating government and restraining government, which all other laws derive from. So it’s the shit. From there, if:

- Congress wrote it: This is called a statute, often called an act. This is how the constitution suggests laws are to be passed, and aside from the constitution, they carry the most weight.

- The courts wrote it: This is called case law, or precedent. The constitution didn’t really grant this power to the courts, SCOTUS gave it to themselves in Marbury v. Madison (1803), by suggesting the constitution gave them this power when it created the courts and ordered them to interpret law. (That said, congress can then rewrite the law—invalidating the opinion. However, if the courts strike down a law as unconstitutional, congress can’t just repass a law with the same unconstitutional premise—they’d need a constitutional amendment to do that.

- The executive (president) wrote it: This is called an executive order. Also not in the constitution. It derives from the president’s authority to execute the law. It was not initially intended to be law, so much as a temporary order. If the president needed to act quickly in an emergency, and congress wouldn’t have time to act, the president needed some power to get shit done, so this is what they came up with. It carries the weight of law, but congress can simply write a new statute invalidating or clarifying it.

- An agency wrote it: This is called a regulation. It is meant to expand upon laws (statutes) congress wrote, not to have been new law created from nothing.

As you can see, congress ultimately has the broadest power to write laws, since they can invalidate any other forms of law, aside from the constitution itself.

This case will specifically hinge around statutes and regulations, so I will make sure to use those terms appropriately. I wanted to make sure you, the reader, understand those distinctions, as this case is all about that shit.

We all know about the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), right? Well, the 1970 Clean Air Act was their jam. It had a rule that said any new major “stationary sources” of pollution had to have a permit.

The idea was, if you had a factory or some large device in a place of business which was putting out pollutants, when it came time to replace that shit or build a new one elsewhere, it required a permit. The permit would then require that the replacement was cleaner than it’s outgoing counterpart.

However, to make life easier, if a company had for instance, a group of major polluting devices that worked in concert together at one location, then one of the components of that group took a shit, the company could replace it without obtaining a new permit, so long as the replacement component didn’t increase the total pollution coming out of the whole “bubble” of devices, as they called it.

It didn’t have to be better, just equal.

So, Chevron went about replacing one of these polluting devices, without upgrading it, under this bubble rule.

Great googly moogly, did that piss off environmentalists—they were none too fucking pleased. They wanted it replaced with a cleaner device.

Since the Clean Air Act (a statute written by congress, remember) didn’t really define a “stationary source” very well, the EPA (a regulatory agency) wrote the “bubble” rule into their regulation to clarify.

In their infinite wisdom, they felt it was a reasonable interpretation of the Clean Air Act’s intent—they were the experts after all. They didn’t think that just needing to repair an otherwise operative system somehow meant a company had to overhaul it completely. Not to mention, sometimes upgrading one component would require upgrading all of them, which could get really expensive.

But of course, environmentalists are the most nauseating group of social justice warriors that ever lived, and they decided to file suit, arguing that the EPA had no right to create this definition out of nowhere, just because it wasn’t well-defined in the Clean Air Act.

SCOTUS however, decided that since the Clean Air Act was ambiguous on this shit, and the EPA were the fucking experts, in such situations the court should defer to their judgement.

This one ruling, and the precedent it set, eventually translated into the idea that all government agencies should be deferred to, going forward, if they made a regulation in their expertise, that clarified ambiguous statutes written by congress, used to create the agency, or written to be regulated by that agency. It became known as the Chevron Deference, and it has been case law ever since.

As you can imagine, with a lot of government agencies, and a shit-ton of regulations, it makes sense that this case has been cited 18,000 times.

Now that you understand the basics of Chevron, let’s move on to our case today.

A group of fisherman (Loper Bright Enterprises) liked to fish in federal waters. But in this country, we often have a problem with over-fishing, where these commercial vessels take so many fish, that those populations of fish can’t reproduce fast enough to keep the species around for others to fish later.

Congress had had enough of this shit. They passed the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA), which is enforced by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), a federal agency, similar to the EPA referenced in the Chevron case above, albeit much smaller.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, “So how the hell does the government make sure that some asshole fishermen don’t overfish an area? They’re in the middle of the fucking ocean!”

No, it’s not with satellites, or sharks with laser beams on their fucking heads. They decided that they would require these fishermen to take a fed out on the boat with them. What made it worse to the fishermen, they had to fucking pay that fed to sail with them.

Imagine, in order to prevent speeding, if the Highway Patrol made you carry an officer in the car with you, and pay their salary for doing so. It’s hyperbolic, and just used to illustrate the point, but you can see why they might have beef with this.

The Magnuson-Stevens Act passed by congress didn’t specify this was the plan, but the NMFS decided to write that regulation, presumably because they couldn’t afford to pay these narks on their own budget. Since Chevron suggested such ambiguous law could rightly be clarified by them, they fucking went for it.

Under Chevron, the courts couldn’t really undo the rules made by NMFS, since the MSA didn’t create a clear rule for them to follow. So that’s why we’re here. To determine if these fishermen have a fair beef with NMFS, and potentially, if a previous SCOTUS was running a little fast and loose when creating this Chevron deference shit.

I’m going to go out on a limb, and explain the politics of this, because why the fuck not.

It’s important to understand a couple things. Remember, regulatory agencies are created by statutes which congress writes, but then the head of that agency is appointed by the president (with the consent of congress), and can by fired by that president, if the president is unhappy with the work they’re doing.

As such, a regulatory agency, is essentially, part of the executive branch.

So the concern, is that there are situations where the president might want congress to pass a statute, but Congress simply don’t have the votes to do so.

So what may happen, is the president looks at the regulatory agencies they oversee, and if one has some tacit connection to the statute they wanted passed, but couldn’t get passed, they tell the head of that agency to write a regulation that resembles the law they wanted. And then—abracadabra-alakazam—you have a law, and you didn’t need congress to pass it.

Since the constitutional principle of separation of powers suggests laws are to be passed by congress as statutes, and not the executive orders or regulations that come from the president, you can understand the separation of powers issue some people have.

People on the right tend to be for limited government, or at least that’s what they say, so they aren’t keen to give presidents this much power.

For Democrats, they argue that if a law is ambiguous about something, it makes sense for regulatory agencies to clarify. They’re the fucking experts, and it’s why congress creates these agencies in the first place.

For instance, imagine congress passes a law that creates the EPA, and says they’re supposed to ensure that the CO2 levels in the air stay within a range that’s acceptable for all current life on earth.

Since they don’t provide an actual number, it’s ambiguous.

So then they rely on the nerds at the EPA to do some science, come up with a number, and make that the regulation. Scientists are open to revising their beliefs based on new information, so if they find out their number is wrong, they can easily update the regulation based on the new science they did.

But you know who wouldn’t figure out what that number is? The fucking courts. They’re law nerds, not science nerds.

Now that you understand both political arguments, you know what I think? They’re both fucking right! They’re making extremely valid points.

Here’s where the politics come in. The left argue that the right are basically rebuking the expertise of the scientists, and instead, acting like they can do just as good of a job interpreting this shit.

They argue that this “separation of powers” issue is swamp gas. But this, I have a problem with.

As you may remember, I wrote about a little case called, National Federation of Independent Business v. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

I won’t re-explain the whole thing here, just know these basic facts.

Joe Biden is not an expert in virology or communicable diseases.

During the COVID pandemic, Joe Biden wanted congress to pass a law requiring everyone get vaccinated, and if not, to wear a mask in public. Presumably for as long as the CDC suggested we were in a pandemic.

Democrats were tacitly supportive of this, but Republicans were like, “Absolutely not! This is America. We’re a free country, and we don’t do shit like this.”

Joe Biden, being the senile by crafty fucker he is, unable to get congress to pass such a law, asked OSHA to make a regulation requiring vaccinations or a mask in the workplace, instead. This effectively would have had almost the same effect as the law he wanted, since the unemployment rate is only about 4%.

SCOTUS overruled that regulation, and Biden lost. But at the time, for whatever reason, they did not overturn Chevron.

So like it or not, there was a real world example of precisely what the right-wing were complaining about, that is quite recent, and quite true. A non-expert president, overstepped his constitutional authority, and bypassed congress to achieve his political goals.

So accusing the right of being conspiratorial and shit, is pretty unfair, in this case.

Anyway, now that you know all that, on to the arguments…

Up first, for the Loper Bright team, represented by veteran SCOTUS counsel Paul Clement.

He opened first, by arguing that the expense of lugging around, and paying for, a fed on a fishing boat isn’t insignificant. It can be as much as 20% of their cost, for a smaller operation.

Not to mention, some of these boats are small, and an extra person gets in the way.

But then, he went after the big fish—the Chevron deference itself.

He spent most of his opening remarks saying that this deference was wrongly decided, and should be abandoned, while maintaining that the Chevron case itself was probably fairly decided.

His argument is that the courts need not determine whether the statute is ambiguous, and therefore a regulatory agency has the unquestionable right to clarify. But instead, that the courts should do what they always do, give their opinion as to what the best reading of the statute is.

Justice Thomas started by asking counsel about mandamus. What is mandamus you ask? I had to look that shit up, too.

Mandamus is when the courts, issue an order to a lower government official, telling them to do their fucking job the way they think that person ought to do it, under the law.

So for instance, if a higher court thinks a lower court have wrongly denied an innocent person their freedom on appeal, and that lower court refuses to take the actions needed to release the person, maybe because they’re arrogant cunts who think they could not have possibly fucked up, they may use a writ of mandamus and basically say, “We weren’t asking, motherfucker—release him now.”

So the nature of his question, is about whether higher courts should tell lower courts how to consider these questions, versus what the opposition wants, which is to defer to regulatory agencies and their expertise, in matters where the law isn’t very specific.

Clement was like, “the constitution gave the power to interpret law to the fucking courts. Then your predecessors, in Chevron, basically gave that power away to the executive branch, since regulatory agencies answer to the president. That’s some grade A bullshit, right there.”

So in summary, he’s saying it’s a separation of powers issue, and the court was wrong to relinquish that power. Unless we’re to amend the constitution, interpreting statutes is the job of the fucking courts.

So if a statute is ambiguous, either congress needs to rewrite it, or the courts get to interpret it. The courts are certainly free to agree with a regulatory agency, but Chevron suggests they shouldn’t even look at the agency’s regulation if the statute is ambiguous, and that shit is wrong.

Justice Sotomayor, digging her heels in early, accused Clement of using some wonderful rhetoric.

She stated that if a statute uses the word “reasonable,” that it’s delegating the authority to define what is reasonable to the agency the statute created.

However, Clement was having none of this shit. He was like, “the law on domestic fisheries is that they shouldn’t incur more than 2-3% of the cost of the catch—clearly they fucking thought about this issue.

So by what reason would your dumb ass think a 20% expense for these fishermen fishing off-shore waters is what congress intended? Have you ever even running a fucking business?”

While I’m sure the regulatory agency feels empowered to do such a thing, their power comes from congress, and congress wrote similar provisions into the statute where they capped it much lower.

So the problem with Chevron is, courts would normally answer statute questions—they’re the fucking experts on that. They should be well within their wheelhouse to look at one, and say, “this dog doesn’t fucking hunt.”

Justice Roberts, coming to the defense of Chevron asked, “It seems to me, you’re arguing that the law is not ambiguous, and therefore Chevron doesn’t apply. Right?”

Counsel Clement was like, “let me put it another way. Chevron says, if you look at a law, and you think you could interpret it in more than one way, you assholes normally decide what the best interpretation is.

That’s your fucking job.

So why would it make sense, in this Chevron context, to all of a sudden be like, ‘Nah, we’ll let the president and his fucking minions sort this shit out.’?”

Justice Kagan chimed in next and said, “Listen you little fuckwit. In normal statutes, if congress writes a shitty fucking law, you’re right. We’re on our own interpreting that shit. We do our best best with our legal expertise.

But if there’s a law that creates an agency, congress has given us a tool to answer such questions in the form of experts. Hell, you could even argue, that the law specifically created the agency to answer those questions. But you’re saying we should shove that tool squarely up our asses and ignore it? I think not.

We’ll use that tool, because a lot of times, they fucking understand the issue way better than we do, and why the fuck wouldn’t we defer to them when congress created them for that purpose?”

Counsel Clement then tried to argue that they had an amicus brief from the House of representatives saying it doesn’t want Chevron. But boy did he fuck up mentioning this, because Justice Kagan fucking drilled him.

She rightly pointed out that congress has the power right now to overturn any aspect of Chevron it wants with new law. Clearly they fucking don’t have the votes. For forty fucking years, they haven’t done so. So you and I both know, it’s just a bunch of your right-wing assholes that wrote that shit, not congress as a whole.

Counsel Clement regained his composure, and put Justice Kagan back on blast with this:

It’s really convenient for some members of Congress not to have to tackle the hard questions and to rely on their friends in the executive branch to get them everything they want. I also think Justice Kavanaugh is right that even if Congress did it, the president would veto it.

And I think the third problem is, and fundamentally even more problematic, is if you get back to that fundamental premise of Chevron that when there’s silence or ambiguity, we know the agency wanted to delegate to the agency.

That is just fictional, and it’s fictional in a particular way, which is it assumes that ambiguity is always a delegation. But ambiguity is not always a delegation.

And more often, what ambiguity is, I don’t have enough votes in Congress to make it clear, so I’m going to leave it ambiguous, that’s how we’re going to get over the bicameralism and presentment hurdle, and then we’ll give it to my friends in the agency and they’ll take it from here.

And that ends up with a phenomenon where we have major problems in society that aren’t being solved because, instead of actually doing the hard work of legislation where you have to compromise with the other side at the risk of maybe drawing a primary challenger, you rely on an executive branch friend to do what you want.

And it’s not hypothetical.

He’s not wrong. The above Biden example, with his OSHA vaccine mandate—is exactly what counsel Clement is pointing out.

Counsel Clement also mentioned a “Brand X” decision often in his arguments, citing it as a prime example supporting his argument.

He’s referring to National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services. A case where the Rehnquist court in 2005, decided that Brand X, a broadband internet company, who was trying to avoid telecommunications regulations by saying it was an internet company, won their case, because the FCC basically stated they weren’t a telecommunications company, and Chevron deference meant the courts were supposed to simply accept that shit—which they did.

His argument was that the courts didn’t agree with the FCC, but the Chevron precedent suggested they had to go with the FCC’s interpretation whether they liked it or not.

Clement seemed to be arguing that this is an opportunity for the court to say, “You know what, we have the power, not these fucking agencies. We’re not handing the power over entirely anymore, we’re taking it back.

His other underlying concern, is that these agencies are vast and varied. So their decisions create new conflicts and precedents, where one agency might decide one way, and another addressing the same exact ambiguity, might regulate in a polar opposite way.

This is in contrast to the courts, who have case law and precedent, which aims to make consistent, things like this.

He even went on to attack congress rather directly, saying that the minority are using Chevron deference to get the president, if they agree with them, to pass laws as regulations, where they know they don’t have the votes to pass themselves. That’s not a soft jab, that’s a straight bomb to the face.

It’s a clear argument that Chevron is leading to direct violations of the separation of powers doctrine our constitution lays out.

Justice Alito asked counsel Clement about what he thinks changed since Chevron was decided. Was it right then, but wrong now?

Counsel Clement first laid out that the courts seem to have embraced textualism more, now.

Textualism just means that the courts interpret the laws as written, not how they think congress may have intended.

He points out, that he thinks the courts were simply wrongly removed from the equation entirely, with Chevron.

If the regulation is based on the expertise of the agency, the courts could and should recognize as much, and let it stand. But the courts should not just assume that’s true and walk away before even examining it.

If the courts recognize that it’s not a regulation based on expertise, but instead, based on politics where the minority and the executive are bypassing congress, the courts should step in and put a stop to it.

Justice Kagan, not a fan of Clement’s position, asked, “we have over 70 SCOTUS cases that relied on Chevron, and over 17,000 lower court cases relied on it. You want us to blow all the shit to kingdom come? What the fuck is wrong with you? The courts will be inundated with new cases, dogs will be sleeping with cars, it’ll be total chaos!”

Clement was like, “I’m not suggesting you blow up anything. No need to revisit a bunch of old cases. I’m suggesting you have the power to interpret law. Not congress. So why the fuck would you entirely give that power to congress, in this context?”

He specifically even said:

I don’t think you actually want to invite, in all candor, that particular fox into your henhouse and tell you how to go about interpreting statutes or how to go about dealing with qualified immunity defenses.

It is rather interesting he’s trying to get the courts to take power back, and the left-leaning justices seem very unwilling to take it.

I know this is disrespectful or arrogant, and I feel bad even saying it, but I think this is a case of political ideology clouding judgement. These justices are toeing a line their political compatriots want them to, instead of thinking critically. But I will try to remain humble, and open to the idea that I’m wrong here.

Clement went on to say, “Listen, I’m not saying overturn a shit ton of cases that relied on Chevron. Again, all I’m saying, is the court shouldn’t remove itself entirely. If the agency can demonstrate to the court, it’s decision is based on expertise the courts don’t have, then the courts should certainly let that shit ride, and not decide it themselves.

But if the courts recognize it’s simple politics, and not expertise, tell them to go pound sand up their ass.

However, Chevron is saying that they shouldn’t even analyze this, and that’s the problem Clement has.

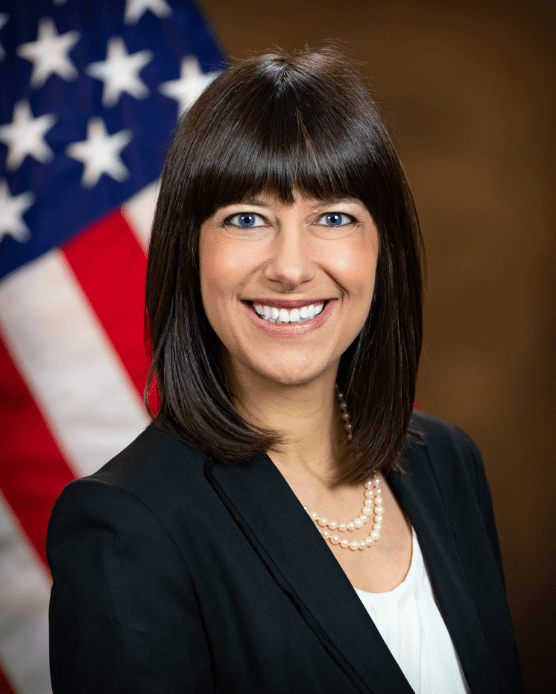

Next up for the government, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar.

She started off by saying the opposition acknowledges that congress can grant authority to agencies, allowing the executive to fill in the gaps they may leave in their legislation for an expert the executive appoints, to fill.

If so, then what the fuck is this grand attack on Chevron? If congress can expressly delegate those powers, why can’t they implicitly delegate them?

She also pointed out stare decisis (latin for “Stand by what’s decided”). The courts generally don’t like to overrule themselves, because then the law is all over the fucking place. Ain’t nobody got time for that.

So she argues, the court could clarify or build upon Chevron, while maintaining the basic principle, as overruling it entirely violates stare decisis.

Justice Thomas started by asking about situations where the law is ambiguous, versus the law is just silent.

General Prolegar pointed out that there are several provisions in the act pertaining to the fishery that talk about how it would be monitored, and by whom. So she argues that the statute isn’t silent at all.

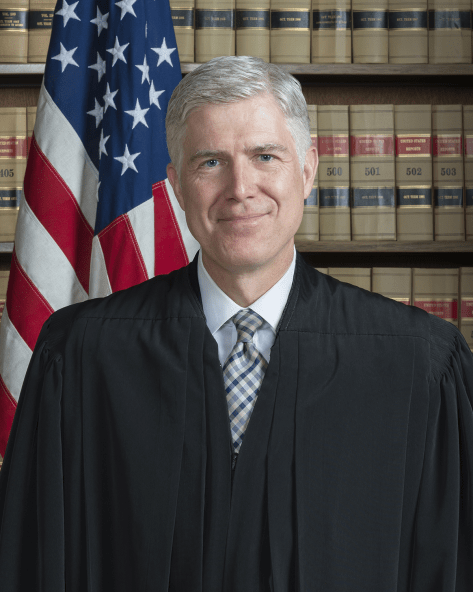

Justice Neil “Golden Voice” Gorsuch was like, OK if you think this statute is clear, and we think it’s clear, isn’t that the kind of shit we interpret every day? Why should we defer that to someone else?

He then asked, “if we all, in this room, think it’s clear, but a lower court didn’t think it was, isn’t that a fucking problem?

Isn’t that evidence that interpreting the statute is almost always ambiguous? If experts on law like us, can come to two different interpretations, there has to be some ambiguousness.

If so, then this Chevron test itself, is too ambiguous? Certainly we’re not supposed to give up on interpreting every statue and related regulation and let agencies handle it? We’re the experts on statutes, not regulatory agencies.

So we should decide if it’s a statutory issue, or an issue of expertise. If it’s statutory, then we fucking decide it. The nerds can handle the other shit.”

He points out that the “ambiguity” trigger in Chevron is so vague, we can’t even decide if it applies to this case or not.

I understand if congress specifically gives the authority to the agency to answer a question in the statute. But you lost me at the idea we should just infer it if the language seems unclear to anyone. That’s crazy talk!”

Counsel Prelogar pointed out that when creating an agency, congress wholly understands its limits of expertise. It purposefully leaves gaps in these laws for these agencies to fill in with regulation, and they have the authority to do so. All Chevron does is recognize that, and honor what congress intended.

Justice Barrett then asked about the previous Brand X ruling, that used the Chevron deference as it’s underpinning. She asked, “Brand X basically said, even if we, the court, have an opinion about the law, and we think it’s better than the regulatory agency’s interpretation, if the court deems the agency’s interpretation is fair or reasonable, it has to go with the interpretation, and ignore what the court thinks is best. But you’re saying we don’t do that, we just use our best judgement based on all the interpretations?”

General Prelogar said she didn’t read Brand X that way. She felt that if the court could see congress did or didn’t delegate the authority to the agency in Step 1 (the statute), then there was no need to go to step 2 (the regulation) and decide if the regulation is fair or reasonable—the court should defer to the agency.

This talk of steps should probably be explained. Chevron was a two-step process.

Step one was to determine if the law was ambiguous or not. If it wasn’t, then Chevron doesn’t apply, and the courts should interpret the statue or regulation, how they see fit.

If the courts believe the statute is ambiguous, then they go to step 2, and determine if the regulation the agency wrote to clear up that ambiguity is reasonable. If it is, then the courts should defer to it, as opposed to coming up with their own interpretation.

Justice Barrett seemed concerned that there’s a facet of step 1 that says they don’t even go to step 2. Barrett’s argument is that the courts should at least go to step 2 and consider the regulation. Step 2 could have some pretty repugnant shit that the courts would never allow.

Justice Roberts asked if Chevron applies to constitutional questions.

Sometimes the court just clears up ambiguously written law, but sometimes it weighs whether the law is even constitutional.

So if step 1 (the statute) is ambiguous, and step 2 (the regulation) is unconstitutional in the court’s eyes, Chevron seems to suggest the courts should still allow the unconstitutional regulation, because they were not supposed to even go to step 2.

But General Prelogar, conceding Justice Robert’s point, suggested Chevron was not meant to block constitutional questions, only to clarify statutory questions.

Counsel Prelogar suggested that they’re interpreting Chevron wrong. It isn’t that the courts don’t even get to step 2. Her opinion is that they always would.

They look at step one and simply determine if the statute is ambiguous. If it isn’t ambiguous, they would ensure that step 2 jibes with step 1, or is constitutional.

If the statute is ambiguous, then they look at step 2, and see if the regulation is reasonable, and presumably constitutional. If it is, then they roll with that shit, instead of trying to interpret it better themselves. If it isn’t reasonable, then they do what they do best—strike that shit and rewrite it.

Either way, they always get to step 2.

After this, Justice Gorsuch and General Prelogar went on a lengthy back and forth about the idea that when considering a statute, congress goes through a lengthy process, where voters can petition their congressperson, and give their opinions before a statute is passed.

But regulatory agencies just pass regulations without telling anyone, necessarily.

Justice Gorsuch is concerned that the people’s government isn’t consulting the people when regulations are passed, and Chevron cuts the people out even more.

He even reiterated the idea that every person gets their day in court, if they want it. But this deference rule sort of says, well, if the law is ambiguous, and the regulation says they don’t, then fuck ’em. They can’t get their day in court.

Justice Sotomayor went back and asked about Clement’s previous argument in regards to the 20% cost of the catch estimates, which are too unworkable, and would often leave these fisherman with no profit margin left.

General Prelogar responded that this 20% number they came up with, were from a land of pure imagination.

This was an estimate provided that it said it could go as high as 20%. In the real world where we live, it falls in the 2-3% like the others he mentioned.

She went on to say, that even if it were higher, the agency provided for waivers and exemptions, if it was truly an unworkable burden for them. So in her opinion, Clement was talking shit.

I think we’ve talked about the Major Questions Doctrine, before in the aforementioned OSHA case. But it’s worth reiterating that the current court feels that major questions are to be answered by congress, not regulator agencies, working as minions for the president.

Again, citing the OSHA case, it was effectively saying the entire working population should get vaccinated, or wear a mask when at work. That’s a major question, as it affects about 96% of the population. The right-wing segment of the court things such questions should be handled by congress, who are answerable to the people if they vote that way, and should not be sneakily pushed through an agency at the president’s behest instead.

General Prelogar knows this court’s majority agrees with this doctrine, so she made an effort to suggest that Chevron is workable within the major questions doctrine, because again, she’s suggesting that Chevron allows for the courts to analyze both steps, the statutory and regulatory, and decide if there’s some sort of over-reach, or other political bullshit going on, and rule accordingly.

Convincing them of that, is probably her only chance of winning this shit.

Counsel Clement did get an opportunity for rebuttal at the end.

He made the point that because of Chevron, members of congress who want to achieve something controversial, which they know would not pass the house and senate, would purposefully make a law ambiguous. Then, they would lean on a sympathetic president to push the agency under their control, to write a clarifying regulation the way that they wanted to pass the law, but couldn’t.

So he feels that overturning Chevron is necessary to shut this shit down.

And overturn it, they did.

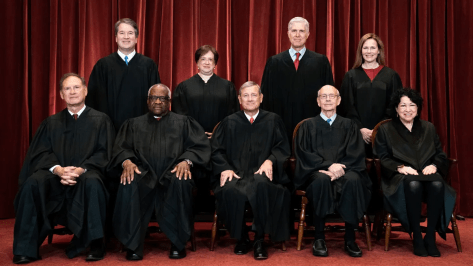

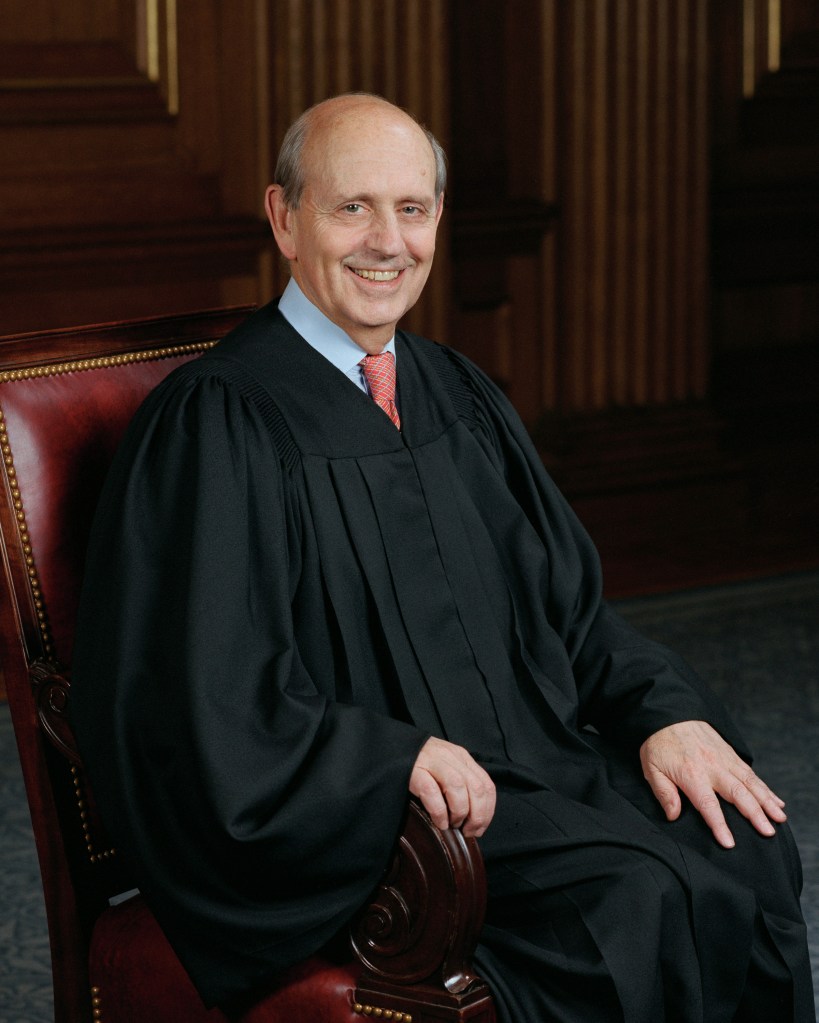

In a 6:3 partisan split, where Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson dissented, SCOTUS sided with Loper Bright, and while doing so, rebuked the Chevron deference.

The majority’s opinion is pragmatic, in my opinion. We’ve covered the political arguments over this case fairly well, and the courts reiterated them.

They agree, that expert opinions, on areas where expertise is warranted, should be considered, and accepted, if they are reasonable interpretations, they don’t violate any constitutional principles, and it seems fair that the statute used to create that agency, give them the power to make such a regulation.

So the left’s argument that the courts are looking to overrule experts in areas that they don’t have expertise, is hyperbolic nonsense, usually reserved for assholes in congress, not the Supreme Court.

So as an example, if congress writes a law asking the EPA to regulate the air in such a way as to ensure healthy air to breathe for humans, and then the EPA writes a regulation saying the air should have no more than 100 parts per million (PPM) of some harmful pollutant, because studies have shown, that more than 100PPM is when it becomes statistically significant to human health, the courts will and should recognize the court is out of it’s bailiwick, and not try to answer that question better.

If the regulation in question however, seems more about statutory interpretation, then the courts can and should consider how they’d interpret it, and if they feel their interpretation is better, they should have no qualms smacking down the regulatory agency.

For example, if congress passes a statute asking the EPA to regulate the air quality, and the EPAs response is to enact some political scheme that bans fossil fuels, that may be a problem. The courts should consider that as a major question, and decide whether that’s an agency’s expertise, or a political question for congress to decide with the consent of the people.

Because, it’s possible fossil fuels could have a place in the market, along side cleaner energy, and banning them completely isn’t really science at all, but a political ideology being put into play.

Hear oral arguments, read about the case, and the opinion here at Oyez.com

Here is another great video from Yale law professor Jed Rubenfeld, explaining it more professionally, than yours truly.

While professor Rubenfeld seems to take an unbiased approach to these issues, here is another, less than unbiased interpretation from Legal Eagle.